Editors love a good reference, and there’s one under-the-radar type of reference book that’s particularly well-suited to editors: the usage dictionary.

Let’s define some terms. A usage dictionary is not a standard dictionary. Your trusty Webster’s New World or Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate is a standard dictionary which primarily contains lexical information: it tells you what words mean. Most standard dictionaries will also tell you a little bit about the context in which the word is most often used, like if that word shows up in nonstandard English. Most general dictionaries will even occasionally include paragraphs at entries like “decimate” and “ain’t” to get a user up to speed on any major usage controversies that might surround that word.

But if you’re an editor who has been feeling the cerebral gears grind as you try to figure out if it’s “There is a large number of teachers in the organization” or “There are a large number of teachers in the organization,” you should know that a standard English dictionary is not going to help you. You’re going to need a usage dictionary.

Usage dictionaries can trace their lineage back to 18th-century writing guides intended to teach upwardly mobile people who didn’t have much formal education how to comport themselves in a higher socioeconomic stratum than the one they grew up in. These letter-writing guides, which used the speech of the upper class as a model, eventually gave rise to books instructing students of all ages on the King’s English and proper grammar, and books which examined the 19th-century uses that began spreading through print journalism. As these books proliferated, it was common for usage mavens to compare their advice to the advice before them; in time, this became the modern usage dictionary.

Like standard dictionaries, usage dictionaries are organized alphabetically. But that’s where the similarity ends. Usage dictionaries give advice not just on words but on grammatical topics that stymie even the most skilled editors—notional agreement, for instance, or flat adverbs. Most usage dictionaries also place those topics and word choices within a broader context for the reader. If you want to know why “infer” and “imply” are often confused, even by the best writers, or how the attitudes towards the confusion of “infer” and “imply” are changing—because they are—a usage dictionary will tell you.

There is one distinction that’s worth highlighting: a usage dictionary will generally give you advice about a contested or confusing usage. This is something that standard dictionaries tend to avoid except in the most notorious or egregious cases: they leave it up to the reader to research, judge, and make choices on their own. But the point of a usage dictionary is to examine a contested or confusing use in depth in order to guide the reader, writer, and editor. And because usage dictionaries give usage advice, they also vary depending on the author and their general attitudes towards English. Some usage dictionaries are more permissive; others are less. Which kind should you consult? Both. They will provide you with valuable content and information, which you can, in turn, use to make better editing decisions.

This article was originally posted to Copyediting.com on 11/11/18.

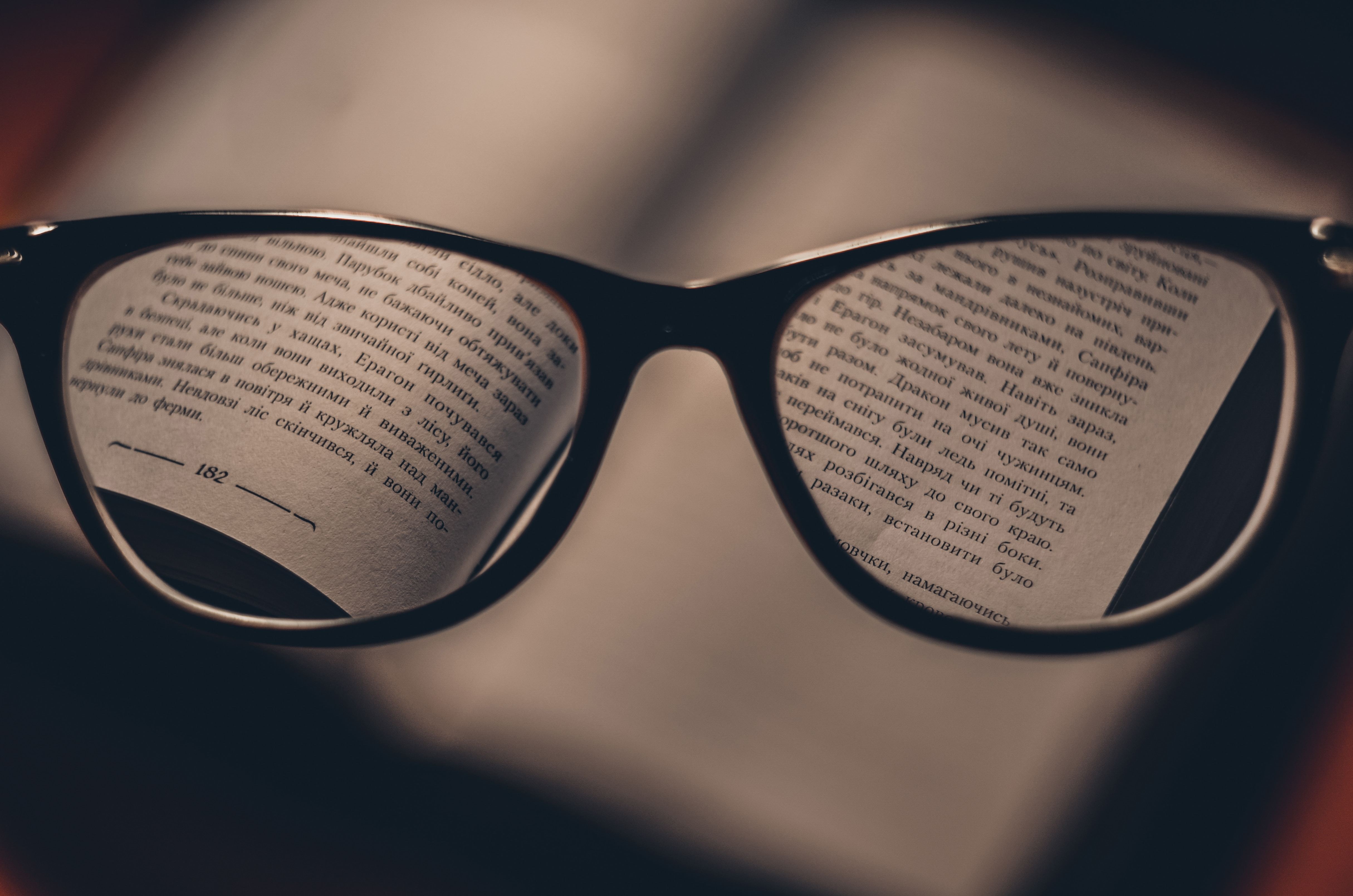

Header photo by Dmitry Ratushny on Unsplash.